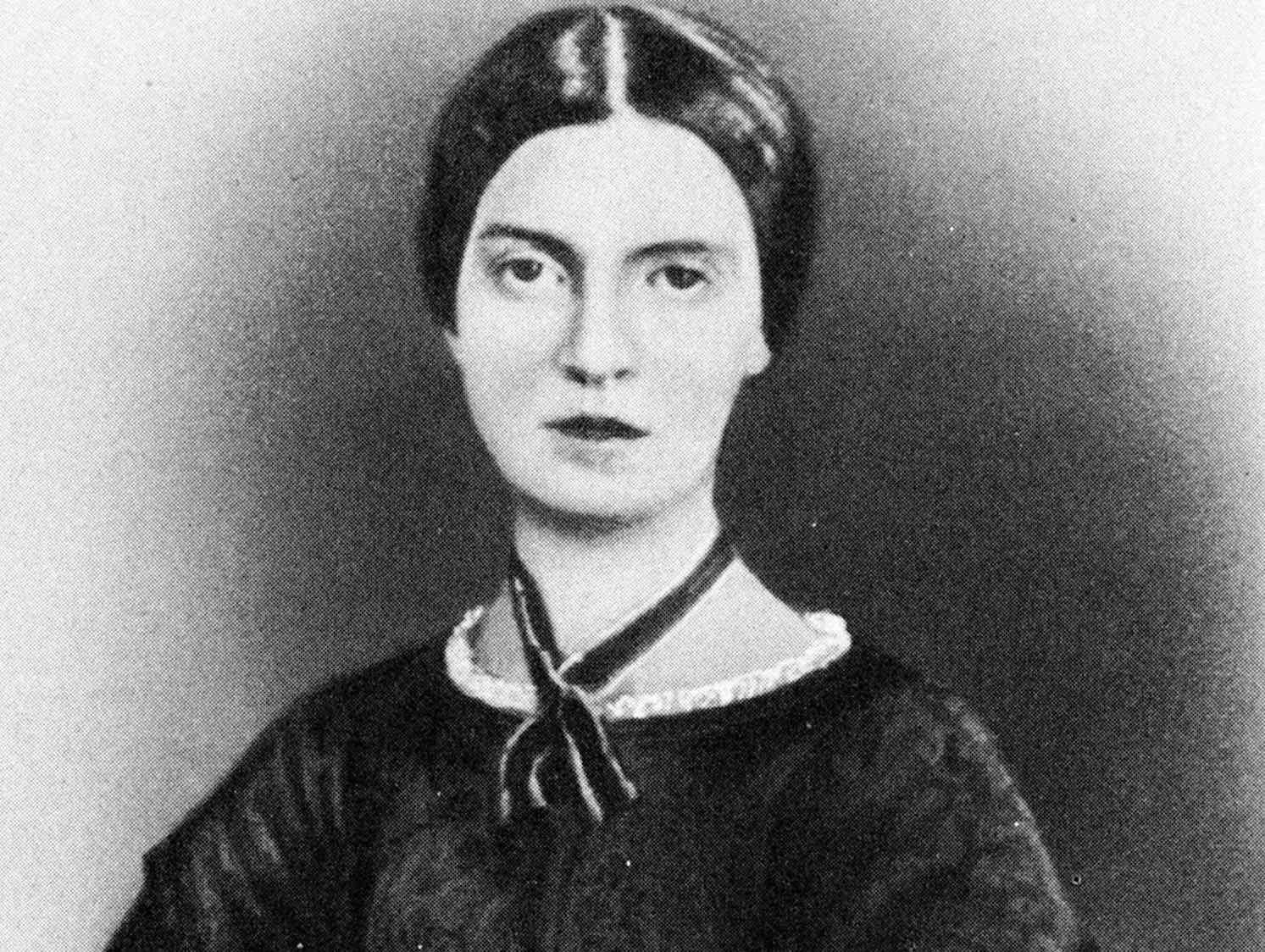

Autobiography of Emily Dickinson

Autobiography of Emily Dickinson is one of the greatest and most original poets in American history. She took her definition as her own domain and challenged existing definitions of her poetry and the work of poets. Like writers such as Ralph Waldo Emerson, Henry David Thoreau and Walt Whitman.

She experimented with liberating representation from conventional constraints. Like writers like Charlotte Bronte and Elizabeth Barrett Her Browning, she created a new kind of first-person persona. The speakers of Dickinson’s poetry, like those of Bronte’s and Browning’s works, are perceptive observers who

understand the inevitable limitations and imagined and imagined escapes of their society. Emily Dickinson

To make the abstract concrete, to define meaning without limits, and to live in a house that doesn’t turn into a prison, Dickinson created a unique oval language in her writing to create the possible. Like the Concord Transcendentalists whose work she was familiar with, she viewed poetry as a double-edged sword. It emancipated the individual, but just as easily left it groundless – Autobiography of Emily Dickinson.

But the literary market offered her work a new realm during her final decade of the 19 th century. When the first volume of her poems was published in her 1890, four years after her death, it was an overwhelming success. After going through 11 editions in less than two years, the poem eventually reached well beyond its initial home audience. Dickinson is known today as one of America’s most important poets and her poetry is widely read by people of all ages and interests – Autobiography of Emily Dickinson. Emily Elizabeth Dickinson was born on December 10, 1830 in Amherst, Massachusetts to Edward and

Emily (Norcross) Dickinson. When she was born, Emily’s father was an ambitious young lawyer. She trained at Amherst College and Yale University before returning to her hometown and joining her father, Samuel Fowler, in her Dickinson’s ailing law firm – Autobiography of Emily Dickinson.

https://onlinestatusquotes.com/who-stephen-hawking-stephen-hawking-bibliography/

Edward also joined his father at the Homestead, his family home built by Samuel Dickinson in 1813. An active member of the Whig Party, Edward Dickinson was elected to the Massachusetts Legislature (1837-1839) and Massachusetts Senate (1842-1843). From 1852 to 1855, he was a representative of Massachusetts to the United States Congress for one term. In Amherst, he established himself as an exemplary citizen, and Amherst prides himself on civic activities, including treasurer of the College, supporter of the Amherst Academy, secretary of the fire association, and president of the annual Cattle his show – Autobiography of Emily Dickinson. Emily Dickinson

Had a Relatively little is known about Emily’s mother, who is often portrayed as the passive wife of her domineering husband. Monson Her few letters, as well as sparse information about her early training at the academy, paint a different picture. Academy papers and records discovered by Martha Ackman reveal a young woman dedicated to her studies, particularly the natural sciences. Emily Dickinson

Three children lived in this house when Emily was young. Her brother, William Austin Dickinson, was born a year and a half before her. Lavinia Norcross Dickinson Who was her sister was born in 1833. All three children attended her one-room primary school in Amherst before transferring to Amherst

Academy, a school that became her college in Amherst. Sibling upbringing soon split. Emily Dickinson

Austin was sent to Williston Seminary in 1842. Emily and Vinnie continued their education at Amherst Academy. According to Emily Dickinson, she was passionate about every aspect of the school: curriculum, teachers, and students. The school is proud of its affiliation with Amherst College and encourages students to regularly attend college courses in all majors including astronomy, botany, chemistry, geology, mathematics,

natural history, natural philosophy and zoology. Provided. As this list shows, the curriculum reflects her 19th -century emphasis on science. This emphasis reappeared in Dickinson’s poetry and letters through her fascination with naming, her skilful observation and cultivation of flowers, her carefully crafted

botanical descriptions, and her interest in her “chemical powers.” Rice field. But science seldom celebrated these interests the way teachers did. In her early poems, she denounced science for her inquisitive curiosity. His system disturbed observer tastes. His research claimed the lives of living beings.

“’Arcturus’ is another name ,” she wrote “I pull a flower from the woods – / A monster with a glass / Computes the stamens in a breath – / And has her in a ‘class!’”. During that time her botany research was clearly a source of joy. She encouraged her friend Abiah Root to join her school assignment.

She took this task seriously and preserved her botanical specimens from her botany textbook for the rest of her life. She learned botany in school because of a popular textbook often used in seminars for women. Her Familiar Lectures on Botany (1829), written by Almira H. Lincoln, dealt with a particular brand of natural history and emphasized the religious nature of scientific research. Emily Dickinson

Lincoln was one of her many early 19th century writers who took the “argument from design” forward. She assured her students that the study of the natural world always revealed God, its impeccably ordered system showing the hands of the Creator at work. Emily Dickinson

Her death took place in Amherst in 1886. After her death, her family found her hand-stitched books or “bundles.” These bundles contained approximately 1,800 poems. Mabel Loomis Todd and Higginson published her first selection of poems in 1890, but a full volume did not appear until her 1955. It wasn’t

until 1998 R.W. She commissioned a Franklin version of Dickinson’s poem. Abnormal punctuation and spelling have been fully restored.